Patient Resources: Coiling

What is coiling?

In the 1990s, coiling was introduced as a way of treating ruptured and unruptured aneurysms without the need for a craniotomy (an operation to open the head to expose the brain). Coiling involves approaching the aneurysm from inside the blood vessel, avoiding the need to open the skull. Small platinum coils are inserted into the aneurysm through the arteries that run from the groin to the brain. The coils remain in the aneurysm: they are not removed. They prevent blood flowing into the aneurysm and therefore reduce the risk of a bleed or a re-bleed. Blood then clots around the coils sealing off the weakened area. It is one of the most commonly performed and most rewarding procedures in interventional neuroradiology practice.What happens before the procedure?

The coiling procedure is similar to an angiogram (an X-ray test to take pictures of the blood vessels) and involves a very small tube (catheter) being fed up to the brain via blood vessels from the groin.However, it is much more complex and is usually carried out under general anaesthesia in the interventional neuroradiology department.

This means you must not eat or drink anything for four to six hours before the procedure. The staff on the ward will advise you on this.

Before you leave the ward, a nurse might shave a small area of your groin at the entry site through which the coils will be passed. If you are well enough, and if you prefer, you might be able to shave yourself.

On arrival at the radiology department, an anaesthetist will give you a general anaesthetic and you will be asleep throughout the procedure.

What happens during the procedure?

The room will have several large pieces of high-technology scanning equipment which are needed to perform the coiling.The interventional neuroradiologist will make a small incision in your groin through which they will insert the catheter into your femoral artery. This is then guided through other blood vessels in your body until it reaches your neck and then into your brain.

Using a guide wire and microcatheter, one by one, one or more coils are slowly inserted into the aneurysm. The coils are made of platinum, are twice the width of a human hair, and can vary in length. The number of coils needed depends on the size and shape of the aneurysm. The largest coil is inserted first and then smaller coils are inserted until the aneurysm is filled. Usually, several coils will be used.

After the whole aneurysm gets filled up by coils, the interventional neuroradiologist will remove the catheter. Occasionally, the entry point in the groin will need to be sealed or stitched. It might be slightly painful and there might be some bruising.

Coiling is a complex and delicate procedure that will take at least three hours and often longer.

What happens after the procedure?

You will probably spend some time in the high dependency unit – usually at least two hours. During this time, regular neurological observations will be performed by the nursing staff. This is to check that you are waking up properly from the anaesthetic. It involves asking you simple questions, testing the strength of your arms and legs, and shining a light in your eyes. Your blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, and oxygen levels will also be monitored.The nurse will check the small wound in your groin for any bleeding and also check the pulse in your foot. This is to ensure that your blood circulation to your legs has not been affected.

It might be that the opening in your artery in your groin is plugged closed after the procedure. This is done with a device called an angioseal.

You will have to lie flat, or at an angle of no more than 30 degrees, for at least six hours following the procedure. This helps with your blood pressure and prevents any excess pressure on the artery which could increase the chance of bleeding at the puncture site in your groin.

Depending on your recovery after this time, you will be able to sit up gradually. The nurses will assist you with this.

Throughout this time, the nurses on the ward will continue to monitor you and carry out neurological observations. Pain-killers will be given for any discomfort or headaches you might be experiencing. You are also likely to have a drip to prevent dehydration, and possibly a urinary catheter.

Because you are restricted to bed rest, you will have to wear pressure stockings to help prevent blood clots forming in your legs (deep vein thrombosis).

What are the risks of coiling?

It is likely that the benefits of coiling will strongly outweigh any possible risks, and your doctor will have discussed this with you fully before you give your consent to go ahead with the procedure. However, as with any invasive procedure, there are certain risks associated with coiling. Possible complications include stroke-like symptoms such as weakness or numbness in an arm or leg, problems with speech, or problems with vision.There is also a risk of bleeding, infection or arterial damage at the entry site in the groin. In all the risk is not more than 3-4% and the risk of death is<1%.

How successful is coiling?

Research is still being conducted to explore the benefits and risks of coiling. Various studies have been published. The largest is the International Subarachnoid Haemorrhage Trial (ISAT) which was established to explore the effectiveness of coiling compared to the clipping of ruptured aneurysms during a craniotomy. The trial involved different neurosurgical centres and a total of 2,143 patients participated. The ISAT trial showed that the long-term risks of further bleeding are low for both coiling and clipping, and the results positively supported coiling as a treatment for ruptured aneurysms, both in terms of survival and in the reduction of long-term disability.Can the coils move?

Once the coils are securely in place they will not move out of the aneurysm.Will I need more coils?

Although the coils do not move, they might settle into the space within the aneurysm. This might mean that more coils are required to block off the aneurysm fully. This is why you will have a follow-up angiogram. Although in literature, about 15-20% patients have some refilling of the aneurysm, in our practice most of them do not need any further treatment. Around one in 20 patients require further treatment.Is it safe to coil aneurysms with difficult morphology?

The interventional neuroradiology practice has evolved rapidly along with the necessary expertise and the technological advances such that the things unthinkable of 10 years ago can be done now. e.g coiling of aneurysms with multiple sacs.

For aneurysms with large size or wide necks, balloon or stent support may be used. A wide variety of them are available now.

Balloon assisted coiling

Balloon assisted coiling Stent assisted coiling

Stent assisted coiling Combined balloon and stent assisted coiling

Combined balloon and stent assisted coilingAn example of balloon assisted coiling is below.

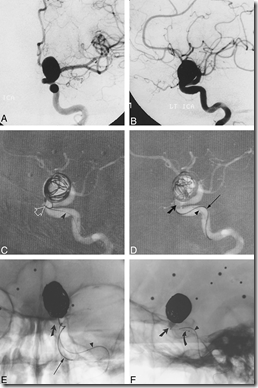

Fig: Balloon assisted coiling. A and B, Frontal (A) and lateral (B) arterial phase images from digital subtraction angiography (DSA) of the left internal carotid artery (ICA) show a large wide-necked aneurysm of the ophthalmic segment.

C and D, Road-mapped live subtraction images of the left ICA (lateral projection) show placement of the first coil. Note the herniation of a coil loop (arrow) through the neck of the aneurysm into the left ICA (C). In D, the balloon (thick arrow) has been inflated across the aneurysmal neck, permitting the framing coils to be deployed within the aneurysm. Arrowheads identify the indwelling 0.010-inch guidewire within the balloon microcatheter. An unextruded segment of a GDC (thin arrow) identifies the course of the coil-delivery microcatheter.

E and F, Frontal (E) and lateral (F) unsubtracted radiographs show deployment of a subsequent GDC. The images serve to orient the viewer with respect to the course of the ICA in relation to the aneurysmal base. The balloon (slanted arrow, E and F) has been inflated within the paraclinoid segment of the ICA, which sweeps lateral to medial across the face of the aneurysmal neck. The supraclinoid segment courses medial to the lower portion of the aneurysmal fundus and is partially obscured by the aneurysm in lateral projection. A small niche of aneurysm lying posterior to the ICA could not be angiographically thrown off the ICA by any of the views attempted. In this respect, the inflated balloon defines the boundary of the ICA lumen and assists the operator in coiling the aneurysmal base. The final segment of coil 14 (thin arrow, E) has been deployed in F. Note the alignment of the delivery wire marker with the proximal microcatheter marker (curved arrow, F). An indwelling 0.010-inch guidewire (arrowhead, E and F) identifies the course of the balloon microcatheter.

G, Mid-arterial phase image (frontal projection) from the immediate posttreatment left ICA DSA after deployment of the 18th GDC within the aneurysm. Coils are present throughout the aneurysmal base; however, minor opacification through the coil interstices is evident.

H and I, Frontal (H) and lateral (I) arterial phase images from the follow-up angiogram 18 months later confirm stable occlusion of the aneurysm.

New materials are being devised day to day e.g bioactive material coated coils which expand after deployment so as to prevent any chance of recurrence.

Tags: Patient Resources

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Share your views...

0 Respones to "Patient Resources: Coiling"

Post a Comment